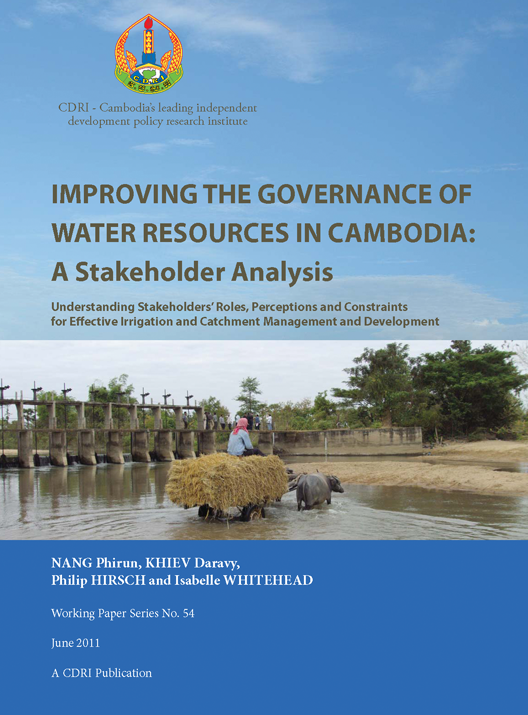

Improving the Governance of Water Resources in Cambodia: A Stakeholder Analysis

Abstract/Summary

Irrigation development and management of water resources present

serious governance challenges for many stakeholders in Cambodia. Farmers,

government agencies, development organisations and the private sector all have

a role to play, yet their roles and responsibilities are not always well

defined. Contemporary ideas on water governance indicate a greater need for participation

and ownership of local resources by the communities that use those resources.

As such, there is a need to refine and rethink the way in which key

stakeholders relate to each other and make decisions on the use of water for

irrigation.

This paper analyses stakeholder roles, relationships and

perspectives with respect to Cambodia’s water resources management, with a

specific focus on irrigation and catchment management. It also examines the

degree of consistency or disparity between different stakeholders, and between

formal stakeholder roles and actual practices. Data from key informant

interviews, field observations, focus group discussions (FGDs) and

dissemination workshops have been analysed to draw out the main issues relating

to water governance stakeholders and to resolve knowledge gaps. It examines water-related

institutions and stakeholder agencies in depth to gain an understanding of

their current capacity and potential. The research findings are presented in a

way that will assist public policy decision-makers to compare and evaluate

policy alternatives.

Several theoretical approaches guided this study, one of which is

the stakeholder typology. Developed as part of the analysis, this perspective

has enabled a broad definition of stakeholders in terms of their relative power

(influence), legitimacy (interest) and urgency. The analysis is also broadly

informed by existing literature on stakeholder relationships and governance

mechanisms, especially as they relate to water governance. This includes

Integrated Water Resources Management (IWRM), which advocates for the proper

coordination and active participation of stakeholders from all relevant

sectors. Its underlying assumption is to consider the social, cultural,

political, economic and ecological aspects of water as being interrelated and

equally valuable.

Findings

The study found that irrigation schemes and rural infrastructure

in Cambodia are often jointly funded by the government and external donors,

with in-kind contributions (such as land and labour) from project

beneficiaries. Water-related issues are handled by several overlapping

ministries and committees with differing, yet specific, mandates, ambitions and

policies. Responsibilities for water resources policy and planning are

increasingly delegated to sub-national authorities and the Provincial

Department of Water Resources and Meteorology (PDOWRAM). This decentralisation of

water management is consistent with the government’s wider process of

sub-national governance reform, recognising the need to introduce new systems

of governance at provincial, municipal and district levels.

The present water governance system, however, is challenged by the

lack of effective feedback mechanisms and coordination among the different

levels of government. Urgent improvements are needed to improve the functioning

of vertical governance mechanisms linking central government, provincial and

local authorities and villages, as well as to improve horizontal governance

mechanisms in support of decision-making across different departments, commune

and village level authorities. For the reforms to be implemented effectively,

the responsibilities of government, especially the Ministry of Water Resources

and Meteorology (MOWRAM), PDOWRAM, donors, local authorities (LAs), Farmer

Water User Communities (FWUCs) and farmers, need to be clear.

Participatory Irrigation Management and Development (PIMD) is

being introduced in recognition of the need for greater community participation

to improve the performance of irrigation systems.1 In the context of Cambodia,

PIMD suggests that FWUCs assume the primary responsibility and authority to

manage, repair and improve existing irrigation systems, and to promote and

guide the development of new irrigation systems. PIMD is accepted as a national

policy in Cambodia and a core strategy to promote participation by farmers in

the management of irrigation schemes.

The sustainability of

irrigation management relies mainly on the performance of farmers and FWUCs,

with technical and financial assistance from concerned institutions such as

MOWRAM, PDOWRAM, donors and civil society organisations (CSOs). Village level

findings indicate, however, a significant disparity between the FWUC’s formal

mandate and its actual effectiveness. Although FWUCs have been granted legal

and administrative responsibility for managing irrigation schemes, the way that

this has been implemented means that most farmers do not feel a strong sense of

ownership over the projects/schemes, and continue to seek LAs’ and PDOWRAM’s

assistance to solve their water issues. The perception that the schemes are not

fully functional also makes it difficult for the FWUCs to collect irrigation

service fees (ISF) necessary for the scheme to remain operational. The lack of

community ownership over irrigation schemes is exacerbated by a perceived lack of

legitimacy of the FWUCs, caused by difficulties and delays with their

registration. Also, despite being independent organisations with a mandate to

coordinate and facilitate local waterrelated issues, FWUCs are hampered by the

fact that they do not have conflict resolution powers. FWUCs have to coordinate

and negotiate with LAs, government institutions and other external organisations

in order to carry out their basic functions.

A range of stakeholders have financed the development and

management of irrigation systems, but sustainable financial arrangements to

support the operation and maintenance of these systems are still lacking. From

1979 to the present, large amounts of funds from the national budget, bank loans

and donor funds have been directed to rehabilitate, construct and maintain

irrigation systems, establish flood protection dykes and install pumping

stations. Financial sustainability of water service delivery should be

achievable because the service to identified users is levied. Many FWUCs

report, however, that the ISF does not cover the cost of operation and

maintenance (O&M). To solve this, the FWUCs have sought financial support

from the government, especially from MOWRAM and PDOWRAM, as well as various

funding agencies. This has led the government to encourage the private sector,

NGOs, international organisations, development partners and donors to invest in

and develop small, medium and large scale irrigation systems and pay for their

O&M.

Better management of water resources in a river basin context

requires effective water governance policy reflecting accountability,

transparency, equity and public participation, with a strong commitment from

all stakeholders. An improved water governance system developed under the

existing legal framework at river basin level would, in turn, support the

capacity of FWUCs, LAs and local institutions to sustainably manage water

resources in a wider social and environmental context.

The implementation of IWRM, PIMD, Irrigation Management Transfer

(IMT)3 and the formation of the FWUCs needs to be undertaken carefully at local

level taking into account the existing political, cultural, socio-economic

and physical features of each specific area. The coordination and

decentralisation work in local communities, however, remains slow, particularly

in the water governance sector, and will need to improve over a period of time

if it is to reach its desired goals. In many areas of the Tonle Sap Basin

(TSB), local people and communities still rely on the coordination or support

of local political hierarchies, such as the commune councils (CCs), district governors

and concerned institutions, to make important decisions. The Technical Working

Group on Agriculture and Water (TWGAW) also acknowledges that some of the

functions of stakeholders are poorly coordinated and there are gaps and

overlaps in functions which need to be remedied within the present public

administration reforms.

In addition to the need for an improved coordination structure and

a more accountable governance system, considerable investment is also needed to

improve the physical infrastructure of existing irrigation schemes. The

irrigation systems will not be technically and financially feasible unless they

are fully operational and provide real and timely profits to farmers.

Recommendations

As part of the participatory approach to this study, stakeholders

were asked to propose practical solutions that could address their concerns.

They described the need for greater technical support and greater clarity at

local levels about the role and nature of IWRM and its relationship to other

policies such as Decentralisation and Deconcentration (D&D) and PIMD.

Although these policies have been implemented at national level, they have not

yet been fully implemented in local communities. Successful implementation of

these national initiatives is dependent on the strength of local governance structures,

local leadership, management capacity and technical expertise.

The research has arrived at the conclusion that there needs to be

some kind of structure to improve coordination at catchment or provincial level

which could also increase the technical expertise available to support FWUCs,

line agencies and other groups without removing their authority to make

decisions about their own resources. On the basis of the stakeholder responses,

this paper outlines a new coordination structure at sub-national level, which

is referred to as the Irrigation and Catchment Management Sub-committee

(ICMSC).

There are a number of different forms that the sub-committee could

take. To stimulate informed discussion and allow for flexibility, the

recommendations below explain the aims and functions of the sub-committee and

identify the key options and considerations to setting up said sub-committee. The

considerations ensure that past lessons inform the development of the new

structure and that the changes support rather than duplicate existing

structures or resources. It is also to stimulate discussion towards a consensus

about how the proposed sub-committee can be given an effective mandate and

remain transparent without diminishing the important local role and authority

of the newly established FWUCs.

These policy recommendations were discussed during the community

level consultations and refined through a series of provincial level workshops

with farmers, FWUCs and representatives from PDOWRAM. They aim to address fundamental

issues relating to the local implementation of D&D policy and IWRM as

identified in the stakeholder analysis.

Recommendation 1: Irrigation and Catchment Management

Sub-committee (ICMSC)

Create Irrigation and Catchment Management Sub-committees (ICMSCs)

at sub-national level to support the coordination of FWUCs, provincial

departments and LAs in making decisions on integrated water resources,

planning, development and management at catchment level. The subcommittee would

assist in building a common understanding among FWUCs, LAs, and provincial departments

about IWRM and D&D policy and support the spatial integration of upstream

and downstream communities. They would provide a basis for the development of

the new governance structures anticipated under the government’s River Basin

Management Policy.

Functions of ICMSCs

The ICMSCs would:

·

Promote ‘bottom-up’ processes for small and medium scale

irrigation scheme management and development projects within a river basin

context taking into account the principles of IWRM, the interests of all

stakeholders and the sustainability of natural resources;

·

Collaborate with concerned institutions (MOWRAM, MAFF, PDOWRAM,

PDAFF), CSOs, provincial governors, LAs, academic and research centres (CDRI,

the Institute of Technology of Cambodia (ITC), the Royal University of Phnom

Penh (RUPP), the Royal University of Agriculture (RUA), foreign universities)

and donors (Asian Development Bank (ADB), Agence Française de Développement

(AFD), the World Bank (WB), Japanese International Cooperation Agency (JICA))

to seek technical and financial support;

·

Provide an avenue to

channel additional technical expertise, including inter-disciplinary advice

from different provincial departments, NGOS, donors and external experts on hydrology

and IWRM so that the sub-committee may function as a ‘service centre’ for the FWUCs;

·

Offer a forum to raise

funds and receive advice from NGOS and donors;

·

Provide an opportunity to resolve conflicts between schemes and

for FWUCs to jointly plan their cropping and harvesting activities through an

informed process based on hydrological and social knowledge;

·

Conduct monitoring, evaluation and impact assessment of water

related activities, water policies and the effectiveness of sub-committee

activities using a participatory approach.

Considerations

In determining the governance structure of the

ICMSC, careful consideration should be given to the following:

·

Lead agency and sub-committee members: Determining the appropriate

government agency and level to lead the sub-committee is important.

Consideration should be given to whether it is best managed at provincial or

catchment level, and whether a given line agency should chair the sub-committee

or whether this would be best done by the provincial office, taking into

account the government’s national policies on IWRM and D&D reform.

·

Mandate and authority: The sub-committee needs a full and

effective mandate but one that is transparent and does not usurp the

decision-making powers of FWUCs and other relevant agencies. Mechanisms for

downward accountability are important so that the FWUCs are represented, are

able to access the technical and financial support that is channelled through the

sub-committee, and are able to call on the sub-committee to exercise authority

when negotiation, arbitration and coordination between FWUCs is required. It

may be necessary for the sub-committee to have an advisory role rather than

full authority in deciding on water allocation at scheme and catchment level,

so that local communities retain ultimate control over key decisions.4

·

Variation between catchments and schemes: Situating the

sub-committee at a provincial/ catchment level provides a more context-specific

structure in which FWUCs, LAs and provincial departments could muster the

authority to make decisions about water resources and irrigation. However, in

each location the sub-committee may take a different “shape”, depending on the

nature of the catchment and the capacity of existing stakeholders. The structure

of each ICMSC will depend on the capacity/ expertise in each location and may need

to be tailored to individual catchments depending on whether they appropriately

overlap with provincial government jurisdictions.

·

Further stakeholder

consultation: A sub-committee should only be established once there has been a

process of joint study, action or consultation. They should not be imposed simultaneously

as “shells” without underlying stakeholder involvement. The establishing of a

sub-committee requires facilitation which is integral to their success.

Recommendation

2: Education and Training

Provide training to local stakeholders,

especially PDOWRAM staff, commune councils, farmers and FWUC committee members

on important laws and policies, so that they are aware of their rights and

duties when using natural resources. The training should cover:

·

Water, Forestry, Fishery, Land and Environment Law;

·

D&D and PIMD policies;

·

Organic Law5;

·

Administrative regulations

and guidelines.

Recommendation

3: Building Local Management Leadership and Capacity

Build the

capacity of FWUC committees and commune councils so that they manage their resources

properly and are able to lead their communities well. Greater capacity is

needed in relation to:

·

Leadership, facilitation and communication skills;

·

Budget allocation and

financial management;

·

Natural resources

management;

·

Project development and

management;

·

Irrigation and farming

systems.

Recommendation

4: Improving FWUC Accountability

Improve FWUC and LA accountability through

strong organisational coordination. FWUC committees have to work according to

the roles and duties set in its statute, despite the limited support funds. Key

areas to take into account include:

·

Encouraging farmers to be aware of the importance of ISF and to

satisfactorily participate in O&M for sustainable irrigation systems;

·

Informing and engaging farmers to participate in irrigation

management and development early and at every stage;

·

Expanding the profit of irrigation to farmers by seeking new

suitable technology for water management and agricultural extension so that

farmers get more products and income;

·

Providing timely water and agricultural information and engaging

farmers to value common interests.

Considerations

Some FWUCs have

raised the issue that if the scheme infrastructure and management capacity are

not improved to meet farmers’ expectations regarding the availability of water

through the scheme, then there may be additional difficulties in increasing

accountability, compliance and participation.

Recommendation

5: Greater Coordination of the Tonle Sap Basin

Decentralisation

in water resources management cannot be achieved if stakeholders, especially farmers,

are not well informed and do not participate in protecting and maintaining

their common property. Some important issues that LAs and concerned institutions

within the Tonle Sap Basin should consider are:

·

Working towards a shared understanding of D&D and PIMD

principles among stakeholders;

·

Delegating appropriate levels of responsibilities such as

planning, implementation, management and decision making in water resources

management and development to local level communities (FWUCs), CSOs, and the

private sector, etc to increase local involvement;

·

Allocating operational and administrative funds to support local

level community functions including accountability and financing or

co-financing; and

·

Reforming and improving stakeholder participation at the Tonle Sap

Basin level, beyond the sub-committee members, by increasing coordination with

local communities, CSOs, private sector and provincial line agencies to

prioritise critical and urgent issues and provide a timely and reasonable

response to them.

Recommendation 6: Proposed Further Research

The case studies and workshops in the three provinces suggested

that the integration of CC members in the structure of the FWUCs (as FWUC

committee members) would help to maintain the legal functions and operation of

the FWUCs. Some local stakeholders mentioned that this integration may also

build up the role and accountability of the FWUC committees by:

·

Empowering FWUCs in their irrigation management roles;

·

Facilitating and coordinating with key relevant stakeholders;

·

Enhancing the sharing of information on water and agricultural

policy;

·

Improving the quality of planning and decision making in

investment /development projects; and

·

Reducing potential conflict between LAs and increasing public

trust and participation. In the above regard, future research could address the

following:

·

How can FWUCs and CCs improve farmer participation or

community-based approaches in water resource management to ensure the

sustainability of irrigation schemes?

·

In the context of irrigation and catchment governance, how can

PIMD and D&D policies be adapted and implemented effectively?

·

How can government-donor-community-private sector partnerships in

irrigation water management be developed? What are the most effective

mechanisms to strengthen such partnerships?

·

Should CC members be included in the management structures of FWUC

committees to provide technical support and authority?